BBC Scotland returns once more to the tragic death of a child cancer patient. This case has run for nine years now, during which Anas Sarwar has cynically appeared with the parents, platformed widely by MSM, to support their understandable need to explain the worst thing that can happen to parents. In one televised election debate, Anas even shouted ‘What about Millie!?’ at Nicola Sturgeon. That led to a vomiting attack nationally. The man has no shame.

Misleading the general public has been regular and frequent.

The headline above is simply wrong. The infection was not fatal in itself but may have contributed to a death.

Contrast the above with the Independent:

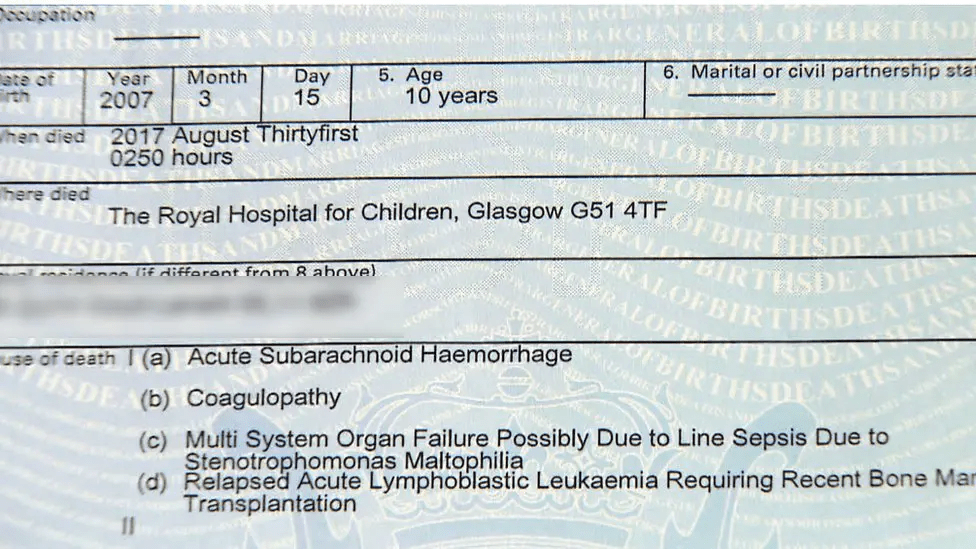

Here is the death certificate:

The death certificate in 2019 lists a Stenotrophomonas infection of the Hickman line among the possible causes of death.1

BBC Scotland then made this even more inaccurate claim:

NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde (NHSGGC) had consistently denied bacteria in the water at the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital (QEUH) was responsible for causing some infections which led to the deaths of patients.

Again contrast that ‘led to the deaths’ with the Independent’s reading:

Milly Main died in 2017 after contracting an infection at the Royal Hospital for Children’s cancer ward on the campus of the QEUH in Glasgow. 2

Sources:

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-glasgow-west-50436138

- https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/scottish-hospitals-inquiry-qeuh-infections-b2902670.html

BBC Scotland’s previous:

On February 12th 2019, I wrote:

Here’s my complaint on 24th January:

‘In a report on deaths at the QEU Hospital, Jackie Bird said: ‘[T]he deaths of two patients from a rare fungal infection.’

This is inaccurate. We knew from the BBC website the same day: ‘The health board said one of the patients was elderly and had died from ‘an unrelated cause’. The factors contributing to the death of the other patient are being investigated.’

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-glasgow-west-46953707

So in neither case did the patient die ‘from’ a rare fungal infection. One clearly died from ‘an unrelated cause’ and the other’s death was still being investigated.’

In the response, the editor admits that the report was ‘wrong’, apologises and tells us that they have had a word with all involved. I know, it’s a small victory after they have managed to inflate the story and to then run it well beyond any reasonable assessment of its importance. As for speaking to all involved, I doubt Jackie has been humbled in any way.

Here’s the full response:

Dear Professor Robertson

Thank you for your correspondence regarding Reporting Scotland. Your comments were passed to the Editor, Reporting Scotland, who has asked that I forward their response as follows:

“Thank you for being in touch about the teatime edition on 21st January.

This is the intro by Jackie Bird to our health correspondent’s report: “The health secretary will meet NHS officials tomorrow, to discuss the deaths of two patients from a rare fungal infection, believed to be linked to pigeon droppings, found at Glasgow’s Queen Elizabeth university hospital. The health board says the hospital is safe for patients and visitors, and has apologised for the disruption caused by measures taken to control the infection. Our health correspondent Lisa Summers reports.”

I have reviewed what was said and the process that led to what was said. The NHS press release which contained information we used started by referring to the investigation into “the cause of two isolated cases of Cryptococcus”; and, several paragraphs later, quoted the medical director as saying: “Our thoughts are with the families of the two patients who have sadly died.”

It appears that the fact that the two people had the infection and that they had died had been conflated by the intro writer into the deaths having both been caused by the infection.

That was not a conclusion that could reasonably be drawn. We were therefore wrong and I apologise for that.

I should add that, at the very top of her report and coming therefore immediately after the introduction, our health correspondent said: “Investigations continue at the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital after it emerged late last week that two patients had died after testing positive for an airborne fungal infection linked to pigeon droppings.” That was entirely accurate.

I am grateful to you for raising this issue and can assure you that we constantly review our procedures in order to improve our service to licence fee payers. In this case I have spoken to all involved and have emphasised the points that you made in your complaint.”

Finally, why is this not being explored?

Is there research evidence that so-called hospital acquired infections are more often brought in by the patient and relatives themselves

Yes, there is substantial research evidence supporting that many so-called hospital-acquired infections (HAIs)—more accurately termed healthcare-associated infections—originate from the patient’s own pre-existing microbial flora (endogenous sources) rather than solely from external hospital sources like the environment, staff, or cross-transmission.Key Evidence on Patients’ Own Flora as a Primary Source

- Endogenous flora dominance: Multiple reviews and studies emphasize that HAIs often arise from the patient’s own colonizing microbes (e.g., in the gut, skin, nasopharynx, or genitourinary tract). These become pathogenic due to hospital factors like immunosuppression, invasive devices, antibiotics disrupting normal flora, or barrier breaches. For instance, endogenous sources account for a majority in many settings, with exogenous sources (including visitors or staff) playing a lesser role overall.

- Specific pathogen examples:

- Staphylococcus aureus (including MRSA): Over 80% of bloodstream and surgical-site infections match strains from the patient’s own nasal or skin colonization. Decolonization strategies (e.g., nasal mupirocin plus chlorhexidine bathing) reduce these risks in carriers, particularly pre-surgery or in ICUs. Trials like REDUCE-MRSA showed universal decolonization in ICUs cut MRSA-positive cultures and bloodstream infections significantly.

- Clostridioides difficile (C. diff): Genomic studies (e.g., in ICUs) show low in-hospital transmission rates; most cases stem from patients colonized on admission (prevalence ~4–15%, rising in some meta-analyses to ~10%). Hospital factors trigger symptomatic infection, but spread from asymptomatic carriers or new admissions is more common than patient-to-patient transmission in many analyses.

- Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., Enterobacter, E. coli, Klebsiella): In cardiac surgery or ICU settings, infections often trace to patients’ endogenous flora amplified by antibiotics, with limited horizontal transmission.

- Bone marrow transplant patients (Stanford study): In immunocompromised patients undergoing transplants, over half of bloodstream infections linked to gut bacteria matched strains in pre-admission stool samples. Minimal evidence of cross-transmission from other patients highlighted self-sourced origins in vulnerable groups.

- Broader data: In ICUs, ~60% of infections are primary endogenous (from admission colonization), ~23% secondary endogenous (acquired during stay but from patient’s altered flora), and only ~17% purely exogenous. Endogenous pathways are amplified by antibiotics, devices, or procedures.

Evidence on Relatives/Visitors as SourcesVisitors contribute in specific contexts but are not a dominant or “more often” source compared to patients’ own flora:

- They can introduce or propagate pathogens, especially respiratory viruses (e.g., influenza, RSV, SARS), norovirus, pertussis, or TB, particularly in pediatric, geriatric, or outbreak settings.

- Outbreaks linked to unscreened visitors (e.g., TB transmission in pediatrics or influenza clusters) have occurred, but these are described as rare for full-scale events. Visitor restrictions during high-community-transmission periods (e.g., pandemics) reduce risks effectively.

- Overall, evidence positions visitors as occasional vectors (often during community surges), with hand hygiene, screening, and limits mitigating spread far more than routine cross-transmission from them.

In summary, research consistently shows patients’ pre-admission colonization as a major (often primary) contributor to many HAIs, especially in high-risk groups, shifting focus toward screening/decolonization on admission alongside standard prevention. Visitors play a role in targeted scenarios but not predominantly. Prevention increasingly targets endogenous risks (e.g., via decolonization protocols) while maintaining visitor safeguards. For deeper dives into specific studies or pathogens, let me know!

49 web pages https://x.com/i/grok?conversation=2012910116874449014

BBC Scotland must absolutely love Prof Robertson. They will need to recruit a SWAT team for the run-up to the election.

LikeLiked by 3 people

The BritNat state desperate to drag this out for their SNP bad stories and propaganda.

Maybe the ‘media’ should be reporting on this instead, it will ‘probably’ mean more cancer cases in Scotland and will ‘probably’ mean more deaths due to cancer in Scotland.

https://c.org/FdN9YVqLHN

LikeLike

Just read more on this and it apparently only applies to England…but of course, as they intend digging deep holes under the Irish sea to dump nuke waste…that will ‘probably’ impact on Scotland as much if not more than it will ‘probably’ affect England.

They say the ‘UKgov is only responsible for energy consultation and policy in England’. Hmm.

Sorry, I just like the word ‘probably’. The English HQ’d BBC as above have used it so why can’t I.

LikeLike

Scotland’s overall national hospital acquired infection rate of approximately 1% compares favourably with England.

The link below gives the results of a survey of 121 NHS trusts in England published on 5 March 2025

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/ukhsa-publishes-latest-survey-on-healthcare-associated-infections

“UKHSA publishes latest survey on healthcare-associated infections

The report finds that overall healthcare-associated infections were present in 7.6% of patients, a 1% increase on the last reported figures in 2016.”

Some of the other percentagrs in this report are much, much higher!

LikeLike

This is a shocking case, which the Unionists have been feeding on for years now. The problem is, as usual, you are preaching to the converted. They don’t care about this. They have got their message out.

LikeLike