Professor John Robertson OBA

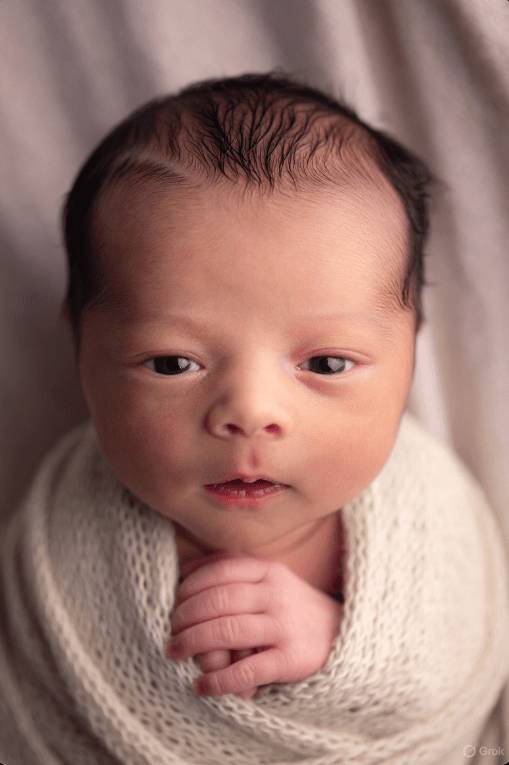

From IVF waiting times in Scotland Quarter ending 30 September 2025 published yesterday:

During the quarter ending 30 September 2025, 362 patients were screened. The 90% standard was met, with all patients attending a screening appointment within 52 weeks of referral. All patients were screened within 26 weeks at the Aberdeen IVF Centre, and most patients at the Dundee and Glasgow IVF Centres also experienced a wait of this length (88.7% and 80.7% respectively).

How does IVF treatment in Scotland compare with that in England?

Scotland has a nationally standardized policy, offering more generous and equitable access compared to England, where funding is determined locally by 42 Integrated Care Boards (ICBs), leading to a “postcode lottery.” This results in significant regional variations in England. Data from the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) for 2023 shows that 54% of IVF cycles in Scotland were NHS-funded, compared to just 24% in England.

Advantages in Scotland: More cycles, shorter/more predictable waits, higher funding rates, and greater equity make it more accessible. This aligns with national goals to reduce infertility barriers, with ~1 in 32 UK births now IVF-related (2023).

Challenges in England: Local variations often lead to stricter rules and longer delays, exacerbating inequalities. HFEA recommends national standardization to match devolved nations.

Sources at: https://x.com/i/grok?conversation=1993409573512778042

What are the wider social psychological and economic advantages of a free generous and universal IVF system like the one in Scotland?

In short, a genuinely universal and generous IVF system like Scotland’s delivers measurable benefits in demographic sustainability, social equality, maternal and child health, psychological wellbeing, and — over a 20–40-year horizon — public finances. The upfront cost is real, but most analyses from jurisdictions that have done it at scale conclude that the societal return justifies the investment.

A fully funded, generous, and universal IVF system — such as Scotland’s current NHS policy (up to three full cycles of IVF for women under 40 and one cycle for women aged 40–42, with no financial means-testing and relatively inclusive criteria) — offers several documented social, psychological, and economic advantages. Below are the main ones, supported by evidence from countries with similar policies (Scotland, Israel, Denmark, Belgium, and the Canadian province of Ontario during its 2016–2023 funded period).Demographic and Social Advantages

- Higher fertility rates and population stabilization

Countries with generous IVF funding consistently have total fertility rates 0.1–0.3 children per woman higher than comparable nations without such funding.- Israel (world’s most generous policy, ~5–8 publicly funded cycles) has a TFR of ~2.9–3.0, the highest in the OECD.

- Denmark (up to three cycles until 2024, now four for the first child) has a TFR ~0.2 higher than Sweden, which has stricter rationing.

Scotland itself saw live births from NHS-funded IVF rise 46% between 2012 and 2022 after expanding access, partially offsetting the national fertility decline.

- Reduced age-related infertility burden

By removing financial barriers, women/couples start treatment earlier (average age at first NHS IVF cycle in Scotland is ~34 vs. ~37–38 in fully private systems such as the USA or England pre-2022 reforms). Earlier treatment yields higher success rates per cycle (40–50% for women <35 vs. <10% for women >42), reducing the emotional and medical toll of repeated failed cycles. - Greater equality of access and reduced class gradient in fertility

In fully private systems, IVF children are overwhelmingly born to high-income, highly educated parents. In Scotland, ~45% of NHS IVF patients live in the two most deprived Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation quintiles (compared to <15% in private English clinics). This narrows the socio-economic fertility gap and reduces future intergenerational inequality.

Psychological and Health Advantages

- Lower psychological distress and regret

Studies from Denmark and Israel show that women who receive publicly funded IVF report significantly lower long-term regret and depressive symptoms than those who are priced out or exhaust savings on private treatment. The Scottish Government’s 2021 patient-experience survey found 87% of NHS IVF patients felt “relieved” that money was not a barrier. - Reduced multiple pregnancies and obstetric complications

Generous public systems can enforce strict single-embryo transfer (SET) policies because clinics are not financially incentivized to maximize pregnancies per cycle. Scotland’s multiple pregnancy rate after NHS IVF fell from 18% in 2008 to ~4% in 2023, dramatically lowering premature births, neonatal intensive care admissions, and lifelong child disability. - Improved child wellbeing

IVF children born after publicly funded treatment tend to be more planned and born into more stable circumstances than children conceived after parents bankrupt themselves on private treatment or give up entirely.

Economic Advantages

- Positive or near-neutral long-term fiscal impact

The most detailed cost–benefit analyses (Israel 2014, Denmark 2018, Quebec 2010–2023) show that each publicly funded IVF birth “pays for itself” within 8–14 years through future tax contributions and reduced welfare/health costs of an aging population.- Quebec’s program (2010–2015) cost ~CAD 70,000 per live birth but generated an estimated net fiscal gain of CAD 60,000–140,000 per child over their lifetime (2020 analysis).

- Israel’s extremely generous policy is calculated to be fiscally positive because of very high lifetime employment and tax contribution rates.

- Reduced healthcare costs from high-order multiples

Scotland saved an estimated £10–15 million per year in neonatal intensive care costs after enforcing SET under the publicly funded system. - Workforce and gender-equality benefits

By shortening the period of infertility treatment and reducing obstetric complications, generous IVF access helps women return to or remain in the labor market. Belgian research (2019) found women who received fully reimbursed IVF were 8–12% more likely to be in full-time employment five years later than women who paid privately or abandoned treatment. - Lower reliance on cross-border reproductive travel and unregulated practices

Countries with restrictive or expensive IVF (Italy pre-2014, Poland, Ireland) see significant “fertility tourism” and higher rates of unregulated egg donation or overseas surrogacy with attendant ethical and health risks.

Summary Table of Key Effects (selected countries with generous public IVF)

| Country/Region | Cycles publicly funded | TFR impact vs peers | Multiple birth rate | % of IVF births to lowest-income quintiles | Estimated fiscal ROI per child |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Israel | Unlimited until 2 children | +0.4–0.6 | ~4% | High (means-tested but generous) | Positive |

| Denmark | 4 (first child) | +0.15–0.2 | <5% | ~40% | Near neutral to positive |

| Scotland (NHS) | 3 (<40), 1 (40-42) | +0.05–0.1 (partial) | ~4% | ~45% | Likely positive long-term |

| England (mostly 1 cycle, postcode lottery) | 1–3 (varies) | Baseline | ~8–10% | <20% | Negative short-term |

| USA (almost entirely private) | 0 | –0.3 to –0.5 vs OECD | 25–30% (private) | <10% | Strongly negative for individuals |

In short, a genuinely universal and generous IVF system like Scotland’s (and even more so Israel’s or Denmark’s) delivers measurable benefits in demographic sustainability, social equality, maternal and child health, psychological wellbeing, and — over a 20–40-year horizon — public finances. The upfront cost is real, but most analyses from jurisdictions that have done it at scale conclude that the societal return justifies the investment.

Sources at: https://x.com/i/grok?conversation=1993410643932987849